by Alan Nichol

Alan is descended from Hunstanworth’s local policeman in the 1880s whose story is told here.

My father, Edward, worked in the Hylton Colliery (Castletown) until he was twenty-one. This was the period of peak production for the mine which had well over one thousand men underground in the mid 1920s. Dad suffered a minor accident deep in the mine when his thumb was crushed by a runaway coal trolley. No doubt influenced by this, and the earlier departure of three of his aunts for Australia, he left England himself in the mid-1920s, leaving behind his family and work mates. The colliery continued production until 1979.

Arriving in Fremantle, he travelled by train with a number of “new chums” up country. It was a long trip but Dad and his mates amused themselves by reading out the strange names of the stations as they passed. The aboriginal names gave them much amusement, just as, I’m sure, Australians would have been equally amused by names such as Hetton-le-Hole. From various clues, it seems that their destination was an area of newly settled farming land near Mullewa.

Dad worked as a drover of sheep for a short period. His kind heart didn’t really suit him for this work. One day he found a sick sheep. The sheep didn’t want to walk back to the yards with the rest of the mob, so Dad carried it. On reaching the yards the farmer said: “Why did you carry it all that way? You should have just killed it, butchered it, and brought back the skin.” Soon afterwards he became affected by trachoma, or “sandy blight.” He then headed east to Newcastle, north of Sydney, where the climate was more suited to Europeans.

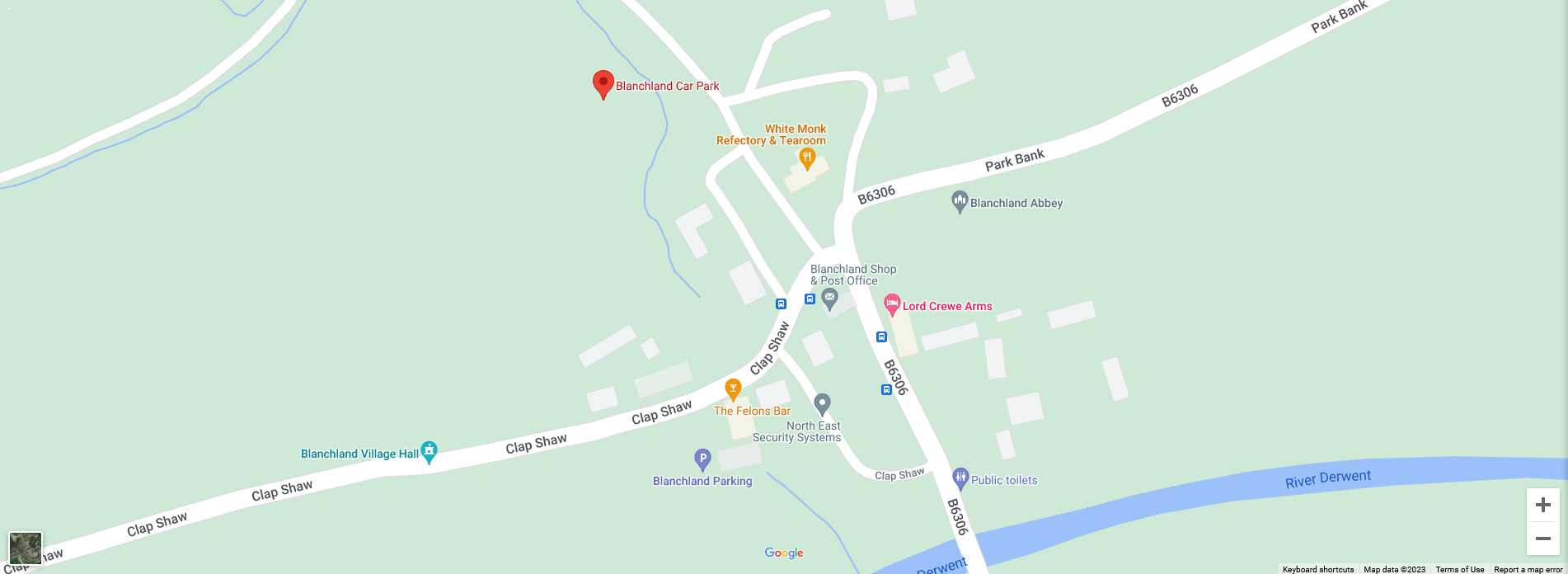

Picture by Stuart Helliwell.

Incorrigible Aunt Barbara

There he stayed with his Aunt Barbara Piper, famous as another member of Mr Campbell’s “incorrigible Nichol family” (Hunstanworth School Day Book, 19 July 1881). Aunt Barbara and Uncle Tom were a “couple of characters.”

They lived next door to the Barnard family. Percy Barnard was a stained glass worker and later became a well-known stained glass artist. After working as a quarryman, Dad got a job with Percy as his assistant. In the process he met my mother, Linda, Percy’s sister-in-law. They married and settled in Sydney.

After a respectable interval, I appeared on the scene. This was in the later years of the great depression. Apparently my first words were bottle-o and rabbit-o, reflecting the calls of street hawkers collecting bottles and selling rabbits, the scourge of Australian farms for many years to come. The search for work led my parents to move to Melbourne. Dad must have felt very much at home here as the climate in Melbourne is dominated by miserable winters, much like “Home,” as Mum and Dad referred to England.

Edward Nichol in his office, circa 1933.

Dad was a great reader and, despite his working class background, believed in self-improvement. He studied bookkeeping, sign writing and typing by correspondence and, with Mum’s help, found himself a job in a large department store where he ultimately became office manager. As a result, far from welcoming the weekend break from school, I dreaded Saturdays. The morning was dominated by working for Dad in his office (ten shillings a morning). The drive across Melbourne in Dad’s Renault was a terrifying experience (Dad was never a good driver), and the boredom of sorting dockets was only ameliorated by the prospect of the horrendous trip home! Our evenings were centred not on television but on doing the Bible readings. I frequently found myself in trouble for daydreaming and losing my place when it came to my turn to read. Nonetheless, Dad and Mum were kind parents.

Dad loved gardening. Our large block had about twenty fruit trees. Dad became an expert on pruning, grafting and experimenting with the espalier technique. Pruning the trees for me was great fun. My supposed job was to collect the prunings, but most of my time was spent making arrows which I fired at Dad with a bow made from string and a sturdy apricot branch. He took all this with amazing good humour. During the war he contemplated buying an orchard in Mansfield, north of Melbourne, but as a conscientious objector he was “drafted” to work in a noxious industry – the Kensington glue factory. He barely survived this work, which involved cleaning vats with benzene, later shown to be an extremely dangerous carcinogen. Returning home each night his clothes, skin and the house in general smelt of boiling hooves and horns. As an Englishman, Dad was used to the ritual of a once-weekly “bath night,” but now the “chip heater” was activated every night to try to remove the dreadful smell. Dad returned after the war to his office job.

Mum died more than 10 years before Dad. He found this loss very hard to take. At his funeral I remember thanking his employer for keeping him on well past retirement age. He replied that thanks were unnecessary and assured me that employees like my father – loyal, hardworking and totally honest – were few and far between.

Our Melbourne home was in a working class area and school reflected the general way of life. Bullying was common, as was the use of the strap by our teachers. I was the recipient of both these. Unlike the bullying, the strap was generally, though not always, well-deserved. Our second year primary teacher managed to combine both bullying and the strap in meting out this form of corporal punishment with gay abandon to all and sundry, and at the least provocation. These memories remain with me to this day.

The John Dan Gene

One of the highlights of my high school days was a great triumph of mine in managing to completely disrupt the maths class without apparent detection. It was a hot day and the schoolyard was almost covered by a plague of common brown butterflies. After finishing our lunchtime sandwiches, a friend and I filled our paper lunch bags with live butterflies. They were so easy to catch that we had no problem in entrapping hundreds. Maths was our first period after lunch. Soon the room was full of the surreptitiously released insects. Our teacher couldn’t control the class and abandoned the lesson. Grandfather John Dan would have been proud of me!

Not surprisingly, I didn’t do particularly well at school, and it was only by the intervention of my kind Latin master that I gained the Leaving Certificate. On the other hand I had a clear idea of what I wanted to do when I left school. I wanted to study chemistry, which had always struck me as the closest thing that you can get to real magic in this imperfect world.

My parents did not have the money to put me through university, nor possibly the inclination, as I wasn’t the easiest teenager to cope with at home (John Dan again?). Thus at age sixteen I started work as a laboratory assistant in the food industry. Two years of what I saw as exploitation of child labour (a bit over the top I admit) saw me transfer my allegiance to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. This was my first exposure to our benevolent state as an employer and mentor. The human face of this benevolence was my immediate boss who later became Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Australian National University. Our work involved the search for new drugs in the plants of north Queensland and New Guinea. A surge of motivation led me to leap out of bed each morning to get to work as soon as possible. This, together, with a sudden realisation that success at the tertiary level meant real study, saw a marked change in my yearly examination results at technical college where I was studying part time.

After four years in this ideal environment I finished my studies and moved to Sydney, my birth place, where I could obtain rather more generous credit for my studies in Melbourne than I could at the rather upper-class Melbourne University. A combination of generous friends and relations (including my parents) as well as a scholarship and waver of fees from the Commonwealth Government allowed me to finish my studies and to graduate with first class honours and the University medal. I felt very proud. The “Emerald City,” as Sydney is often called, smiled on me. I met my life-long partner, Margaret, and found full-time study very much to my liking. Three further years, and I completed the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

A Hundred Years On

Following the usual pattern of overseas “postdocs,” my wife and I spent two years in Canada before being driven from the prairies by the excesses of the northern hemisphere winters. On our return, I worked in medical research at a major Sydney hospital for three years whilst the smile in our benevolent government’s face changed to something like a scowl. Research funding dried up very quickly. I took a teaching position in biochemistry at my old alma mater. For various reasons this didn’t work out and our small family moved to Wagga Wagga in inland New South Wales. Twenty-six years later (and exactly one hundred years after my great grandfather’s retirement from the Durham Police Force), I retired as the Head of the School of Food and Wine Science and Associate Professor in Biochemistry at Charles Sturt University.

My retirement interests include gardening with Australian native plants, cooking, boating, French language and culture, ringing church bells, bridge, reading and asking myself pointless questions about why I am here on this beautiful planet. My wife and I share these interests as well as learning about ourselves from family history and enjoying the successes and activities of our two sons and our two grandchildren.

Wagga Wagga – New South Wales, Australia – October 2008

Alan and Margaret Nichol…not at all incorrigible!