The village in verse

Perhaps because of its spectacular natural setting and the romantic tales that have grown around it, Blanchland and the surrounding area have been the focus for much poetic expression.

I certainly wouldn’t feel qualified to judge what is good or bad verse, though for modern tastes, many of the following lines are rambling and laboured and totally lacking in any subtlety of meaning!

What they may not possess in poetic merit, the Blanchland poems certainly make up for in sincerity of feeling – and in their way they’re valuable historical records of the places, events and people that have gone before.

A Lifelong Love

The cokeworks labourer who loved Blanchland

Blanchland schoolboys, possibly circa 1860. George Carr could be among these young scholars, and the Master could be Thomas Iley, who taught in the village for many years. Photo given by Allan Shaw of Ilkley.

Of all the poets who have attempted to express the delights of Blanchland in verse, George Carr has to be the most prolific.

He was born in Blanchland in 1850 to a young unmarried woman called Hannah, and was brought up by his grandmother, also called Hannah. He married at 24, and moved to Crook, County Durham, where he was employed in the cokeworks for around 30 years. He and Elizabeth (nee Oyston) had lots of children, but George always remembered his happy childhood in Blanchland and loved to return to the village to see old friends and reminisce about times gone by.

George’s best known poem is Bonnie Blanchland, written around 1890, more than 300 stanzas of everything Blanchland, including the massacre of the monks, the day the lead miners nearly blew up Baybridge, and the annual show.

You can download the full, illustrated pdf version of Bonnie Blanchland below.

The year before his death in 1916, George again wrote a poem about Blanchland. This time it was a journey to the village by car, in those days a novelty to most people. To read this poem, click on the image to the left.

By Motor to Bonnie Blanchland by George Carr

Auden’s Ambo

A place of ‘sweet memories’ for great English poet

Wystan Hugh Auden in 1928

“More champagne!” is not a cry you hear that often these days in the bar at the Lord Crewe Arms, but bubbly was the 23-year-old WH Auden’s preferred tipple on a night in Blanchland in Easter 1930, bashing out Brahms on a clapped-out piano ’till the wee small hours.

Arguably England’s finest 20th Century poet, Wystan Hugh Auden had a lifelong love of lead mining and the North Pennines, and this fascination would be reflected in his work, even in the later years when he became an American citizen.

Born in 1907, the young Auden’s letters to Santa must have made interesting reading; at the age of 11, one of his Christmas books from his mother is EH Davies’ Machinery for Metalliferous Mines. He first visited Rookhope with his family at the age of 12, and he says in The Dyer’s Hand, a collection of essays written in 1962 that: “Between the ages of seven and 12, my fantasy life was centred round lead mines.”

Although the lead mines were long gone by the time Auden began writing, they – and their passing – are a constant theme for him.

Experts believe he had his artistic epiphany atop Bolts Law, majestic heather-clad hill that looms above Ramshaw. It’s thought he is referring to the Sike Head Chimney in part of his poem “New Year Letter 1940”.

Contributing to a series of travel articles for American Vogue in 1954, Auden writes about “Six unexpected days in the Pennines”, recalling a trip he’d made the year before. Of Blanchland he says: “It is a number of years now since I stayed at The Lord Crewe Arms, but no spot brings me sweeter memories.”

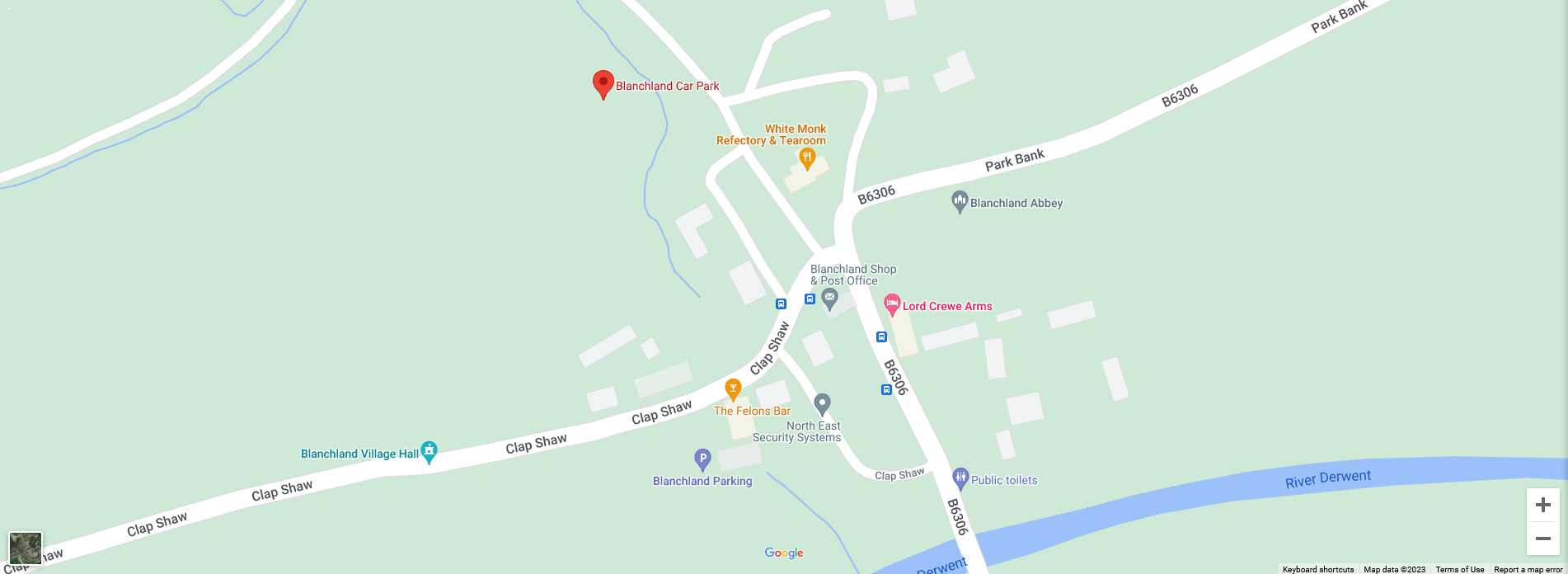

Auden had a fascination for North Pennine placenames, and seems to have relished creating a rich and resonant collection of fantasy names in his poetry which allude to real locations. For many years the true location for Auden’s ‘Pressan Ambo’ was a complete mystery, but the late North East writer and translator Alan Myers argues persuasively that Pressan Ambo is actually Blanchland.

He suggests that the only placename in the North Pennines similar to “Pressan” is The Presser, the water pumping station above Ramshaw and about two miles from Blanchland. ‘Ambo’ has implications of ‘both’ or ‘two’, suggests Myers, and could refer to the ‘twin’ villages of Blanchland and Hunstanworth. Other references to the Lord Crewe Arms and the village’s archway which used to be the main entrance for vehicles, point compellingly towards Blanchland as Auden’s Pressan Ambo.

The Presser, Ramshaw Annette Ellis

Whether or not this is so, it’s clear that Blanchland – and the North Pennine lead mines – held a special place in the poet’s heart.

Information from WH Auden – Pennine Poet by Alan Myers and Robert Forsythe, published by the North Pennines Heritage Trust

A Tale of Two Brothers

A tale of two brothers: Thomas and John Graham Lough

One would achieve international renown as one of the finest sculptors of his time, the other would die a pauper in a County Durham workhouse; the Lough brothers were born more than 200 years ago into an ordinary rural working class family, but their lives would take extraordinary – and very diverging – directions.

John Graham and Thomas were two of 11 children born to William and Barbara (nee Clemetson) Lough, John Graham being born on January 8 1798 and Thomas on May 7 1801.

John Graham Lough shot to sculptural stardom while still in his twenties; he’d travelled to London to study the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum in 1824. By 1826 he was exhibiting at the Royal Academy, and was feted by London society and bankrolled by wealthy patrons.

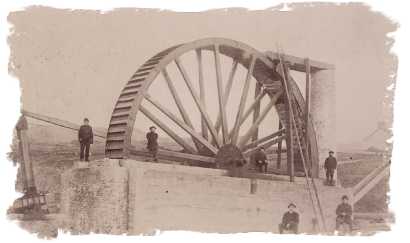

The Ramshaw Flood… subject of Thomas Lough’s 1848 poem

His works include the Collingwood Monument at Tynemouth, others that grace the interiors of St Paul’s and Canterbury Cathedrals, statues of Victoria and Albert at the Royal Exchange, and even the lions at the foot of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square.

By contrast, his brother Tom’s career took the course that was more or less expected of a young man from a humble home; he went into his father’s trade, and probably his grandfather’s before that.

Local historian in the 1960s Fred Wade writes a pitying account of Thomas Lough’s wasted talents: “He served his apprenticeship as a blacksmith in his father’s shop at Greenhead and later was employed as a blacksmith at the Ramshaw Lead Mines, but he soon left his honourable means of earning a livelihood and took to a life of roaming. He was an able artist, poet and musician, and might have made a name for himself in any one of these professions, but he wasted his talents, and became what we in North West Durham call a “Rodney”. All he earned at fairs, shows and hirings by his fiddle went in tobacco and strong drink, which was more to him than nectar to the gods.”

Other records suggest Tom’s decline wasn’t quite as definitive as Fred Wade believed; Fred says Lough roamed the counties of Durham and Northumberland for more than 50 years, but he’s listed in the 1839 account of Blanchland’s Riding the Bounds as one of dozens of ‘runners’ who joined in with the ‘perambulations’ of the estate boundaries on foot (and admittedly much beer was consumed at the rest points and in the pubs along the way).

One other interesting record which has come to light is an 1831 article from “The New Sportsman” magazine, in which the author who is visiting the area for the grouse shooting, tells of a chance meeting on the road to Blanchland…

“By degrees, we learned that his name was Lough, and to the inquiry if he was any relation to the Sculptor of that name, he replied, scratching his head – “Why yes, I believe I’m his father, at least so they tell me.” At this point, John Graham Lough had been working in Rome for three years; he’d probably not seen his parents for some time!

According to the sportsman’s account, John Graham Lough was rocketed to national and international attention as a sculptor because the owner of Minsteracres Estate, George Silvertop, had seen the lad’s potential and helped him make his way. “I remember his debut in the Metropolis,” says the author, “and the apparent determination exhibited by part of the press to publish as many mis-statements respecting him as possible. He was lauded to the skies, in a manner enough to ruin any young artist…”

So John Graham Lough had a meteoric rise to celebrity status, and back home in Blanchland, brother Thomas, at nearly 30 years old, still seems unable to find a clear direction…

The grouse shooter continues his account with their arrival in Blanchland: “A very excellent Inn is kept here by Mr Blenk, where the sportsman finds every accommodation and attention. Lough occupies a small neat cottage about 50 yards out of the square, to which having accompanied him, he showed us several of the earlier productions of the son, and related several instances of his talent; but we were unable to learn from him, that any former member of the family had exhibited a similar genius.

“There is another son who, I understand, has since turned his attention to the arts, but who had not then discovered in what department of science his genius reposed.”

Here, Thomas is mentioned only in passing, and despite his skills as a musician, poet and artist, at the age of 30 he is already in the shadow of his renowned sculptor brother.

In his 1884 book Historical and Descriptive Poems, Joshua Lax confirms that Thomas did indeed feel that his brother was stealing his thunder: “Poor Tom often told me how jealous he was when the Squire (George Silvertop) entered the cottage lest John should claim some of his drawings…”

It must have galled him to have to namedrop his brother, the famous sculptor, in the subtitle of his poem The Ramshaw Flood, published in 1848, presumably to sell more copies of his own work. But by then, perhaps he was grasping at any celebrity he could.

In contrast to Fred Wade’s conclusion of alcoholism, though, Mr Lax’s account suggests that Thomas’ chaotic vagrancy may have been due to mental illness, which in the mid-1800s would have gone undiagnosed and untreated…

“Among his peculiarities was an utter hatred to the colour red, an aversion to looking-glasses, and a dislike to any room where there was a flood of light and strong reflection. He also disliked to see a hole in the wall, and would, if allowed, stuff it with paper, turn the looking-glass around, and cover up any shining ornament which offended his eye.

Byron’s Mazeppa: Thomas Lough would draw scenes from the poem and sell the illustrations in local pubs.

“A friend,who knew the Lough family well, told me that Tom commenced his wandering life as early as the year 1826 or 1827. When the engines for the Messrs. Annandale’s paper mills were being laid down, the engineers engaged in the work used to frequent the Bridge End Inn, Shotley Bridge, in the evenings, where Lough often turned up to entertain them with the Jew’s harp, and fiddle, and by reciting his own and the poems of other authors, and by airing his drawing talents… His favourite subjects in drawing were The Ninevite Bull – a mythical animal with a human head and five legs – The Flying Ass, Group of ‘Bacchanalians’, Byron’s Mazeppa and a group containing two human figures and several savage-looking horses; the latter of which I have in my possession; it is not only vigorously drawn, but is a wonderful conception, and, with other productions of his, shows how his mind, stored with the literature of Greece and Rome, teemed with imagery.

“His favourite authors were Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Gibbon, Byron, and Burns; the first of whom he had read earliest and most earnestly, and in consequence his mind received the strongest of its colours from the great Greek.

“His performances on the violin were of the most comical character… Placing the fiddle between his knees when in a sitting posture, he used the bow vigorously, and thence flowed strains which, as fame informs us, caused, in a certain inn, in Weardale, I think, panes to fly out of the windows, the pot lid to fly up the chimney, and a child to leap from the cradle of its slumbers, and dance in a most unaccountable manner. It was here, too, I believe, that he drew a fox with a piece of charcoal on the hearthstone, which the terrier dogs with the company attempted to seize, mistaking it for a living reality. Poor Lough used to tell me those absurd stories with a solemnity that could not be exceeded by the gravest Musselman.”

The death of the Lough brothers’ mother Barbara in 1852 may have sealed Thomas’ itinerant fate. The year before, he is still holding down his job as a blacksmith and still living in Blanchland with Barbara. When she dies, there is nothing to keep him in Blanchland, no-one to keep him on the straight and narrow.

In the 1861 Census, Thomas is found living in a hayloft in Iveston, Lanchester. Seemingly at a loss as to how to categorise him, the census enumerator creates a special section – “List of persons not in houses” – and Thomas Lough is the only one on the list. He’s clearly gone down in the world, his occupation recorded as “Blacksmith’s Labourer” and afterwards – perhaps at Lough’s insistence – “artist” has been added.

Although in very different circumstances, the two brothers died within a year of one-another, John Graham a wealthy family man in London having carved a place for himself in history, Thomas a pauper in Lanchester Workhouse in 1877.

John Graham Lough in his studio by Ralph Hedley: According to Joshua Lax in his 1884 book Historical and Descriptive Poems, this was the sculptor’s ‘make or break’ moment.

John Graham Lough’s room was too small for him to use his chisel on his statue of Milo, so…”With the recklessness of a bold genius reduced to desperation, he actually broke through the ceiling of the room above him, and made for himself sufficient space to work at his statue. The owner began to take steps for instituting legal proceedings, and even consulted Mr. Brougham (afterwards Lord Brougham) for this purpose. Brougham went to look at the Milo, and see for himself what Lough had done… The news of the strange affair soon spread, and, before long, the whole street where Lough’s room was situated was lined with the carriages of ladies and gentlemen, who had come to view the place, and to see Milo.”

The Ramshaw Flood by Thomas Lough

If it had happened today it would have been remembered as “08/08/08”: on August 8th, 1808, the North East of England was lashed by a violent storm. John Sykes in his Historical Register of Remarkable Events wrote a lengthy report on the devastation: chimneys destroyed and bell wires inside Newcastle houses melted by lightning; pavements forced up by rushing floodwater; people, sheep and cattle killed by the electric fluid – and this: “A new smelting mill at Derwent-heads, near Blanchland, was nearly swept away by the flood, together with a large quantity of lead ore.”

Thomas Lough would have been just seven years old at the time, old enough perhaps to have a terrifying memory of being woken in the night by the shrieking power of the storm raging outside. But it would be in his work as a blacksmith at Ramshaw Lead Mines more than 30 years later that he would have heard the old men in Ramshaw relate the dramatic detail of the night, which would provide him with the material for The Ramshaw Flood.

Today, “The Bard of Derwent’s” overblown rhyming couplets and hyperbolic classical references lead the reader to expect terrible human calamity, death and destruction on a leviathan scale. The reality is more mundane; ‘Dent’ loses two of his most precious possessions – his pipe tobacco and his pet canaries!

The strength of the storm certainly seems to have warranted Thomas’ melodramatic descriptions; the floodwaters forced away rocks and boulders to reveal a valuable bounty of lead ore, silver and sparkling fluorspar.

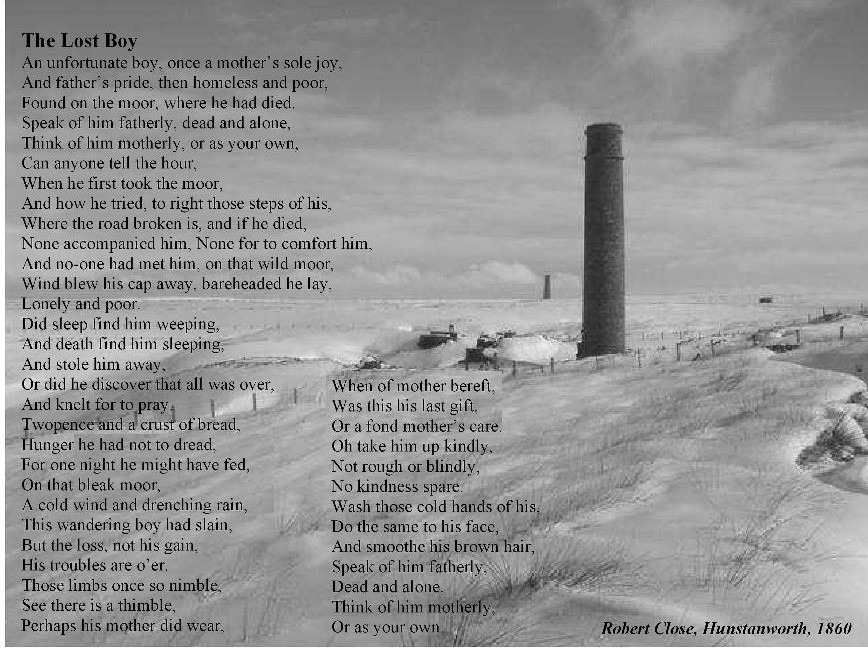

Tragedy On The Moors

A boy’s lonely death

Local historian Fred Wade recounted this sad tale in the 1960s…

"In 1860 an Irish boy 12 years of age ran away from his home at Blackhill and tramped up the Derwent Valley with the intention of going to Rookhope to seek work. He was last seen at Baybridge on a very stormy day and a few days later his dead body was found lying on a flue which carried the smoke and fumes from the Ramshaw Smelt Mill to a chimney situated on the hill top. In his pockets were found a crust of bread, two pennies and a woman's thimble. His mother had died shortly before he left home, and perhaps he took the thimble as a memento of her. The boy's body was not identified and he was buried in Hunstanworth churchyard in the clothes he was wearing when he met his death."

It was supposed the boy, cold and tired, had found a warm spot by the flue on the bleak and desolate moors above Ramshaw. While he rested, he had breathed in the deadly fumes escaping from a leak in the flue’s stonework, never to awaken again. Robert Close, the then master of Hunstanworth School, was moved to write this poem about the tragedy. The simple, tender words must have echoed the grief of the whole community…

The Lost Boy

"An unfortunate boy, once a mother's sole joy,

And a father's pride, then homeless and poor,

Found on the moor, where he had died.

Speak of him fatherly, dead and alone,

Think of him motherly, or as your own,

Can anyone tell the hour,

When he first took the moor,

And how he tried, to right those steps of his,

Where the road broken is, and if he died,

None accompanied him, None for to comfort him,

And no-one had met him, on that wild moor,

Wind blew his cap away, bareheaded he lay,

Lonely and poor.

Did sleep find him weeping,

And death find him sleeping,

And stole him away,

Or did he discover that all was over,

And knelt for to pray.

Twopence and a crust of bread,

Hunger he had not to dread,

For one night he might have fed,

On that bleak moor,

A cold wind and drenching rain,

This wandering boy had slain

But the loss, not his gain,

His troubles were o'er.

Those limbs once so nimble,

See there is a thimble,

Perhaps his mother did wear,

When of mother bereft,

Was this his last gift,

Or a fond mothers care.

Oh take him up kindly,

Not rough or blindly,

No kindness spare.

Wash those cold hands of his.

Do the same to his face,

And smoothe his brown hair,

Speak of him fatherly,

Dead and alone.

Think of him motherly,

Or as your own."