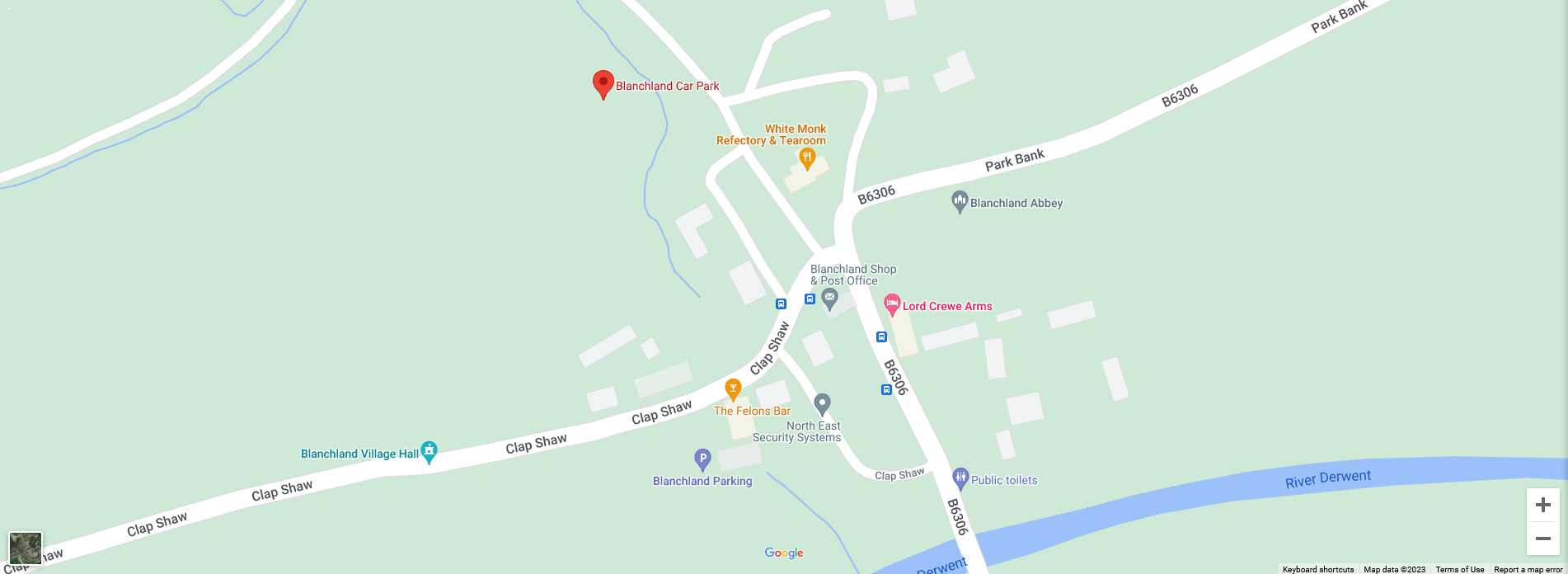

Navigate to:

Murder Most Foul

Today the ruined farmhouse of Belmount is like many lonely spots out on the moor above Ramshaw, the wind sighing sadly through the rotting timbers of old window frames and roof joists. But Belmount has a fascinating, dark secret which it has kept to itself for more than 130 years; if those tumbledown walls could speak, they would tell us who murdered Robert Snowball in his workshop on New Year’s Day, 1880.

Tales of Derwentdale, a collection of local folklore published in 1902, gives one account of what happened in the story “The Blanchland Murder”. Young farmer Robert Snowball leaves the remote farmhouse – where he lives with only his father and the housekeeper – to do some joinery in the byre, with plans to go and visit a friend later on that evening. The next morning he is found dead by the housekeeper after being hit with extreme force in the back of the head with a sledgehammer. The following Monday – the 5th – an inquest is held at the house of PC Ferguson in Ramshaw and Robert Snowball is buried the next day in Blanchland churchyard. Later on the 6th, the Snowballs’ housekeeper Jane Barron is arrested and put in the police cell at Ramshaw.

The case attracts national press attention; on January 12 The Guardian’s correspondent writes that he had been up to Belmount… “It would be almost impossible for a stranger to find the house even in daylight, and it would be impossible for him to find it after dusk. He would lose himself in the attempt.”

The Guardian report fills in the detail that the Derwentside Tale leaves out.

Robert Snowball had taken on the tenancy of Belmount in May 1878, and had lived there with his aged parents, John and Ann. Robert’s mother had died just six or seven weeks before the 26-year-old’s own life would come to its abrupt and grisly end. On November 18 1879 the father and son had taken on Jane Barron, aged 27, as housekeeper.

The Guardian report follows the Tale fairly closely, lingering perhaps a little longer than necessary on the forensics… “The whole of his teeth were forced out”. The blow from the 3lb iron hammer with its 3ft long shaft … “had been struck with such force that half of the hammer head entered the back of the skull…”

Because old John Snowball was considered “infirm and tottering”, the finger of suspicion didn’t even move vaguely in his direction. Jane Barron was a strapping woman of five foot six inches… “possessed of broad shoulders and a deep chest”. There were holes in her story as big as the hole in Robert Snowball’s head: she claimed she’d seen blood dripping from the barn ceiling, but the police said it couldn’t have seeped through the flooring of the workshop, and if it had, not in the place she had indicated.

Her clothes had been stained with blood; no-one had been seen in the area for three days before the murder, and neither old Mr Snowball nor Jane Barron had made any mention of the farm dogs barking to alert them to a stranger approaching. It has to be either Jane Barron or old Snowball.

And yet the Guardian reporter says: “When charged at the Stanhope Police Office by Superintendent Henbron (the policeman’s name was actually Thubron – but don’t forget this is a Grauniad report), Barron answered, after an interval of over a minute, “I haven’t murdered anyone, and I haven’t seen anybody murdered.”

The local police, the doctor and the coroner, unused to dealing with such a strange and serious crime, were way out of their depth. In the byre at Belmount the day after the murder, the doctor thinks at first that Robert has “…had a fit, burst a blood vessel and expired.” Despite some misgivings, he sends a telegraph to Stanhope requesting a coroner to attend an accidental death – and as a result a full three days elapse before the police arrive.

“She said, “Waa’s all yon blood coming down the byre?” I said it would be from the sheep that was cutten up in the loft.” – John Snowball.

It gets worse; when they do get to Belmount on the Monday morning, Mr Snowball senior has mopped up the blood in the workshop… “The old man also said that he had thrown the water out upon the ashpit, and on searching there the police found some of the teeth of the murdered man.” Potentially vital evidence has gone forever. Anyone who may have been around Belmount on the fateful day has had three days to make good their escape.

Another possible flaw in the process is highlighted by The Guardian: “The prisoner had been committed on the capital charge at a magisterial inquiry at which there was only one magistrate present. Mr Justice Stephen, in his charge to the Grand Jury, had urged them to throw out the bill and leave the case open to any further evidence that might come out. This course was not taken, and the prisoner was put upon her trial.”

At the Durham Assizes the following April, the Guardian says the crowds mob the doors of the court, excited to hear what the verdict will be.

In court, old Mr Snowball says Robert had teased Jane Barron that day at the tea table about a suitor, called White, he thinks, and she had blushed and appeared unhappy about it. Claiming to be confused, the old man changes his evidence and says he remembers she had followed Robert out to the barn, and reappeared 10 minutes later, flushed and putting her head in her hands. Giving evidence herself, Jane Barron says that neither she nor the old man left the house until she went out to milk the cows.

Despite all the circumstantial evidence, Jane Barron is acquitted, no motive forthcoming, the jury’s decision depending on whether they believe the old man or not, and the suggestion that some “person unknown” who had borne a grudge against Robert Snowball had lain in wait in the barn to smash him from behind while he worked away at his joinery. Who, though, would have a grudge against a 26-year-old who lived in a remote farmhouse with his old Dad?

It’s not as if he has accumulated lots of enemies in his short life; the granite cross in Blanchland churchyard reads… “in affectionate remembrance” and Tales of Derwentdale says that at Robert’s interment… “there was a very large attendance of persons from many miles round the district.”

One name crops up two or three times in the columns and columns of feverish verbatim reporting – but somehow the details are never fully explored. Jane Barron’s former employer, George White of Hedley, had sent Jane a letter saying he was coming to Belmount to see her, and Robert Snowball had heard on the local grapevine that White had actually made it as far as Blanchland two or three weeks earlier but had been unable to find Belmount up on the moors. Giving evidence, Thomas Green of Blanchland said Robert Snowball had been talking about his new housekeeper when he’d popped into The Angel for a New Year’s Day lunchtime drink just hours before his murder. He’d said George White – ‘her sweetheart’ – was going to be visiting Jane later on that day.

A year after these terrible events, the Census records for 1881 show us that old Mr Snowball is still at Belmount, with younger son, John, in charge and another housekeeper looking after them. Jane Barron is still a housekeeper, but in Boldon, far away from the storytelling and sensationalism that must have enthralled late night fireside gatherings for many years afterwards.

But she finds – as have many people since then – that there’s no escape once you’ve been thrust into the media spotlight. The murder becomes a topic for ‘Pitman Poet’ Tommy Armstrong in The Blanchland Murder, and more seriously Jane Barron’s name crops up in the Newcastle Courant in January 1881; she is sueing both the Consett Guardian and the Durham Advertiser for libelling her by saying she’d been admitted to a lunatic asylum – and she’s awarded more than £40 (equivalent to about three years’ wages in her housekeeper role).

There are lots of questions even now: If he was on his way to Sandyford to visit the neighbours, how did Robert Snowball end up in the byre, seemingly dying without a struggle? If Jane Barron really had followed Robert Snowball, and come back face reddened after the sound of a fall in the byre as John Snowball said in his altered evidence, didn’t he notice the blood splashes on her at that point? Was George White, Jane Barron’s former employer from Hedley, ever questioned and did he go to Belmount that evening as Robert Snowball had been telling his friends? Strangely none of the newspaper reports of the time report these vital details.

The speculation went on for years – now and again a newspaper would report a rumoured ‘deathbed confession’, but these always proved unfounded. Whoever really murdered Robert Snowball all those years ago, and why it happened at all, the old walls of Belmount farmhouse aren’t telling.

The Day in Question

Belmount, New Year’s Day, 1880

10am: “On Thursday, the 1st January, my son Robert left home to go to Blanchland.” – John Snowball giving evidence at the inquest, reported in Northern Echo, Jan 22 1880.

Blanchland village square, with the Angel Inn to the left. Postcard courtesy of George Ellison.

11.40am – 12 noon: Report from the Hexham Courant, Saturday January 10:“Robert Snowball was in Mr Davidson’s public house with Mr John Brown and Mr Green…Deceased then inquired of Mr Green what kind of girl Mr Bell the grocer and draper had got and Mr Green replied that she was a very decent sort of girl as far as he knew. Mr Snowball asked her name and being told that her name was White he said: “Yes that is her name. Where does she come from – Hedley Mill?” and is told: “No, Hedley on the Hill”. “What makes me ask is her father comes to see our housekeeper. He was here a fortnight ago and is coming tonight. I know that for a fact. When he was here a fortnight since he got drunk, and could not get any further than here. I do not know much about him, but Taylor of Baile Hill tells me he knows him, and that he is a shortish and darkish complexioned man. If you put in here tonight you will perhaps see him.”

Thomas Green, joiner, of Blanchland, giving evidence at inquest and reported in Northern Echo, January 22:“I was in The Angel Inn, Blanchland, at about twenty minutes to twelve; the deceased came in… and remained there about a quarter of an hour or 20 minutes; he had half a glass of whisky. The he got on his horse and left; he was perfectly sober.

“In answer to me, deceased said he had got a very decent, useful girl as his housekeeper. He also made the remark that her sweetheart was coming to see her that night – that his name was White – from Hedley.”

Belmount today: The milking byre with loft above was nearest in picture, while the kitchen was the window to the right of the porch.

1pm: “He said he would be home at the “height” (middle) of the day. He returned at one o’clock. I and my son and Jane Barron had dinner together. After dinner deceased said to Jane Barron, “I have got the whole affair about the lad,” I think she replied, “You haven’t. He mentioned a man’s name – it might be “George” – and her face struck red. She muttered something, but I didn’t catch what she said. I went to bed, and got up again at three o’clock. “At about four o’clock we had tea together. After tea deceased said he had a notion of going to Sandyford (the next farm).” – John Snowball giving evidence at the inquest, reported in Northern Echo, Jan 22 1880.

This is the point where John Snowball makes “corrections” to his original statement…

“When it was about dusk I went out around part of the buildings, but saw nobody about to the best of my recollection. I had a dog with me, and there were other dogs on the premises… I went round the north side of the buildings towards the fell. I went “fornenst” (opposite) the door of the loft… the door was shut. When I went in again the deceased was in the kitchen, as far as I can recollect.” – John Snowball.5.15pm: Robert Snowball leaves – John Snowball’s evidence.

5.30pm: “I last saw Robert Snowball alive when he went out of the house alone. He said he was going to Sandyford, Thomas Murray’s, a nephew.

“I remained in the house until milking time, have past six o’clock on the same evening, and John Snowball was in the kitchen, where I was busy ironing. He was sitting by the fire, and never went out during that time.” – Jane Barron giving evidence at inquest, reported in Northern Echo, Jan 24 1880.

Northern Echo Jan 27 1880:

John Snowball has… “flashes of recollection alternating with periods of oblivion”… “…in his first statement he distinctly said the housekeeper did not leave the house, and he never mentioned hearing the thud.”

Again, the following is a “correction” to the original statement… “At the time deceased went out Jane Barron was in the kitchen. After he went out I was sitting on a chair, and Jane Barron came and reached up on the mantelpiece, where I think the matches would be. She then went out, and as she was shutting the door, she took a good look at me… I heard a jingle in the passage, which sounded like lifting a lantern. It was eight or ten minutes before she came back. Before than I heard a loud noise which attracted my attention. I heard a fall in the loft. When she came back, to the best of my recollection she came back and sat by the end of the table with her head between her hands… I noticed her face then, and I thought it was redder than usual.

“I remember her going out at half-past six o’clock and she came back about seven.” – John Snowball.

6.30pm: “At half-past six pm I went to the cowbyre and milked the three cows. Directly I went into the cowbyre I noticed blood dropping, drop by drop, quickly from the boarded floor of the loft above the cowbyre, just behind the cows, just a little bit within the door, from a part of the loft floor, not far from the closet in the loft. The drops of blood came onto my head. I had a candle-lantern with me, and I knew it was blood by putting my hand on my head and then looking at my hand by the light of the lantern…” – Jane Barron.

7pm: “I milked the cows before going into the house, when, about seven o’clock, I told John Snowball about the blood dropping… he said he thought it was only from where deceased had been butchering the sheep.” – Jane Barron. “She said, “Waa’s all yon blood coming down the byre?” I said it would be from the sheep that was cutten up in the loft.” – John Snowball.

10pm: “John Snowball went to bed about 10pm. I sat up in the kitchen alone until about three o’clock the next morning without ever going outside the door, waiting for deceased’s return, but he never came.” – Jane Barron.

Northern Echo Jan 27 1880:

“Would she not have avoided the blood of her victim… would she at once have informed the father of the circumstance which alone enables us to fix the hour when the deed was done? Even if she had got smeared with blood, not expecting that it would drip through the floor, her obvious policy – supposing she was guilty – was to say nothing about it, but wait till the old man went to bed, and then wash the blood stains out. She did nothing of the kind, but, making no attempt at concealment, mentioned the incident on her return to the house… She told the coroner, the police and the neighbours exactly the same story, and betrayed no sign of having a guilty conscience to suffer or a false part to play.”

The Victim

What was Robert Snowball really like?

Northern Echo, January 12

“The unfortunate young man Robert Snowdon (sic) went to the Belmont farm a complete stranger. It is said that he was too particular against people travelling or making a footpath over a certain, almost barren field, and had threatened the offenders by telling them that he would inform the gamekeepers or the local policeman.

“It is not known whether he was paying his addresses to any person or not, but it is strongly rumoured that he was. It was also rumoured that he was going to be married to Mrs Barron, but from what can be gleaned it had only been rumour, although he had spoken somewhat freely when last at Blanchland.”Northern Echo, January 14

The reporter visits Belmount…”My knock at the door was answered by a comely, middle-aged woman, who, upon stating my errand, communicated with someone inside. This someone turned out to be Mr John Snowball, brother of the murdered man, and said to resemble him strongly in features, though somewhat smaller of stature. He is of light complexion, slight side whiskers of an auburn tinge, and with a gentlemanly air about him rather above the general run of farmers’ sons in the locality.”

The Father

Lightning strike affected John Snowball’s memory

Northern Echo, January 14

Reporter visits Belmount and has a meal with John Snowball: Old Mr Snowball is apparently about seventy years of age, and the recent murder of his son appeared to have had but a very slight, if any effect upon his nerves. He is tall and slim, and his figure slightly bent with age; otherwise he seems hale and hearty, and walked with none of that tottering gait with which he has been credited.Northern Echo, January 22

John Snowball at inquest: When I gave my evidence on the first meeting of the inquest I was in great distress of mind. There are certain statements I made then which I wish to correct. Between the 1st and the 5th of January I talked the matter over with my neighbours… I have had an accident, by which I lost my health, about thirty years since, and my memory is not so good as it once was. I never told anyone that I didn’t hear a thud on the floor. I have a brother-in-law named Robert Taylor, but I never told him or anyone else that I didn’t hear a thud. I never heard such a thud before. John Snowball is talking about the “fall” that he hears in the byre – though whether he was ever asked how he knew it was a “fall” and if it was such a loud “thud” why he wasn’t concerned to find out what had caused it, is not recorded.

The Suspect

“Aw havn’t murdered anybody…”

Northern Echo, January 12

“The housekeeper, Mrs Jane Barron, was the widow of the late John Barron, a leadminer and small farmer. His father, John Barron, was a smeltor, and occupied the same land. John Barron jnr. was a quiet, inoffensive young man, and had three or four brothers who had a great respect for their brother’s widow, and considered her a member of the family.”

Northern Echo, January 14

“She possesses great firmness and determination, and is of a taciturn disposition. She lived as a servant with Mr White, Hedley West Riding, for three months. She left in November 1878, and went home unhired, as many others were at that time, and hired at Hexham May hiring to Mr Pearson. She left that place last November, and had then gone to keep house for the unfortunate man.”

Illustrated Police News, January 17

“Jane Barron is described as a strongly-built woman, with deep chest and broad shoulders, and apparently possessed of above the average amount of strength of women. The only thing she lacks seems to be intelligence. She is very slow of speech and comprehension. On being formally charged she exhibited no emotion of any kind, and after an interval of fully a minute, she drawled out, “Aw’s clear on’t. Aw havn’t murdered anybody, and aw hav’n’t seen anybody murdered.”

Northern Echo, January 19

“John Dodd of Hedley North Farm: “Jane Barron was the eldest girl of a large family; she was sent to the village school at Hedley to receive what education her parents were able to give her… “she was of a quiet, reserved and retiring disposition…” “Since she left school she has been engaged as a farm servant, and has lived with a few of the most respectable and well-to-do farmers in the district; for it was only farmers in good position that could secure her services, and she invariably received the largest wages which were current.”

Northern Echo, January 24

“Deceased did not then, or at any other time, take any liberties with me. George White was never at Belmount on January 1st, or at any other time since I have been there as servant that I am aware of. I have had letters from him twice, addressed “Belmount, Blanchland,” promising to come and see me. On the first of January, about three o’clock in the afternoon, when deceased was joking me about Geo. White, he said he had found that White had been as far as Blanchland, which is under three miles from Belmount, three weeks ago, but could not find his way across the fells to see me. White knew that I was in service with deceased, and that he was a young man.”

Inside Belmount

Journalist’s ‘exclusive’ with Snowballs before the inquest

Northern Echo, January 14

The reporter visits Belmount and meets with old John Snowball, his younger son John and a “comely, middle-aged woman…”

“The household… were at dinner, which was set upon a moderate-sized round table in front of the fireplace – a good, old-fashioned kitchen range. A cordial invitation to join them at the meal was readily accepted by me, and an extra plate and knife and fork were speedily laid.

“The furniture of the room was not what could be termed elegant, and indeed, there seemed to be a lack of cleanliness or order about the apartment, which was quite the opposite of comfortable, as might have been expected when the housekeeper was in the lock-up.

“In addition to the round table upon which the dinner was set, a square deal one, covered with unwashed plates, dishes, cups and saucers, baking tins, and scraps of bread, occupied a position close in front of the window, the view from which was partially obscured by a short muslin curtain.

“That side of the kitchen fronting the fireplace, was occupied with a gigantic piece of furniture in the shape of a combined dresser and chest of drawers, while a longsettle, cushioned, ran down the other side. To the rafters hung bags, bunches of dried herbs &:c., while a fiddle and bow hung upon a nail in one corner.

“Over the mantelpiece were a pair of brightly-polished steel spurs, together with a bit of the same metal. An eight day clock, clean in outward appearances, was by far the neatest article in the room.”

The Aftermath

What happened to them all?

It is impossible to imagine life going on as normal at Belmount, not just because of the violent death of Robert Snowball, but also with the intense media interest in the months and years that follow. When old John Snowball dies in 1883, a newspaper rumour immediately circulates that he had made a deathbed confession to the killing of his son, but neighbours steadfastly refute the gossip.

The new housekeeper, Elizabeth Nicholson, marries John Snowball jnr, Robert’s younger brother, and they move to Benfieldside with their family. Belmount has new tenants, and the events of that dreadful New Year’s Day in 1880 begin the slow drift into history.

Following her acquittal, Jane Barron becomes housekeeper for farmer Mr Lowdon of Downhill Farm, Boldon. In the January of 1881 she takes two newspapers to court – the Consett Guardian and the Durham Advertiser – for claiming that she had been admitted to a lunatic asylum along with Joseph, her brother. Once again the case goes in her favour, and she wins more than £40 in damages – about three years’ salary in her housekeeper role.

On July 2 that year Jane Barron marries James Charlton of Greenside, a labourer 11 years her senior, and despite being recorded as ‘Widow’ in that year’s census which was taken on April 3, on her marriage certificate she is very specifically down as ‘Spinster’. The following two census returns show in the following 20 years she lives at Blackhall Mill and has two children, John William born in 1887 and Jane born in 1891.

But the end of Jane Barron’s story is far from the picture of cosy domesticity the census returns up to 1901 would suggest; on the eve of her silver wedding anniversary in 1907, the troubled Jane Barron storms out of the house following a violent argument with her husband. She is found drowned in the River Derwent, taking with her to the grave any guilt she may have had for the terrible deeds at Belmount Farm.

More than eight years on, and this Leeds Mercury filler of July 18, 1888 shows that speculation is still rife.

This handwritten footnote to the story of the Blanchland Murder in an old copy of Tales of Derwentdale explains the “sad end” of Jane Barron’s life.

Delays and Errors

Series of mistakes means vital evidence is lost

Northern Echo, January 23

The second day of the inquest upon the body of Robert Snowball, continued at the Police Station, Ramshaw-on-Derwent, by Mr Coroner Graham.

Coroner: When you first visited the deceased’s body what conclusion did you come to? Did you come to the conclusion that it was the result of an accident or of violence?

Witness, Dr William Montgomery, Blanchland: I couldn’t account for the injuries having been caused by such an accident as a fall.

Coroner: What was your conclusion?

Witness: That the injuries must have been caused by violence. It was between nine and ten o’clock when I saw the body on the morning of the 2nd January. I rode off at once to Blanchland.

Coroner: Did you then send off the following telegram to Superintendent Thubron at Stanhope: Robert Snowball, Belmount, accidentally met his death by falling and fracturing his skull. Get Humphrey George to procure coroner immediately.

Witness: I did send it.

Coroner: Tell me if anyone authorised you to send such a telegram?

Witness: No, we agreed.

Coroner: What was your object in sending that message?

Witness: To procure a coroner immediately.

Coroner: What was your object in saying that it was an accident?

Witness: It is a great mistake I have made.