A wartime fighter plane that crashed on lonely moorland above Hunstanworth and sank without trace into a peatbog has been unearthed almost 66 years to the day.

Many people in the area who were children or teenagers at the time still remember the Spring day in 1942 when a Spitfire came down on Stanhope Common.

The pilot was 25-year-old Harold John Appel of the Royal Canadian Air Force (below right), stationed with Number 81 Squadron at Ouston in Northumberland.

The aircraft he was flying on that fateful day was a single seater fighter, Supermarine Spitfire Mk IIA, serial number P8563. The plane was also called “City of Leicester I”, because it was what was known as a ‘presentation aircraft’, and had been purchased by the Lord Mayor of Leicester’s Spitfire Fund. According to its record card, the plane had been with Number 315 (Polish) Squadron the year before and, flying P8563, Sergeant Aleksander Chudek had destroyed three Messerchmitts over France in August 1941.

The RAF investigation into the moorland crash tells how P/O Appel takes off from RAF Ouston at 18.22 hours on the evening of Friday March 27 1942 to patrol Seaham Harbour with his section leader Flight Sergeant Peter Anson in another Spitfire. From the very start, there is something wrong; taking off at Ouston, P/O Appel cannot not be contacted on his radio. Time and time again, F/Sgt Anson tries contacting the other pilot but gets no reply; P/O Appel is not able to transmit or receive.

Both Spitfires are returning to base when P/O Appel breaks close formation when entering very low cloud. While F/Sgt Anson lands at 18.55 hours, P/O Appel is coming out of breaking cloud and flying very low to determine his exact location when he crashes into high ground.

Two of the artefacts found at the crash site: the Spitfire’s ammunition box and fuel cap.

One eyewitness who went to the crash site that evening was Blanchland lad Tommy Everitt (who sadly died in 2007), who was just 12 at the time. The local police, Home Guard and RAF hadn’t arrived on the scene by then. More than 60 years later, Tommy told Philip Smith of the local amateur group Air Crash Investigation and Archaeology (ACIA) that he saw the cockpit of the plane totally buried in the peatbog with one wing on the surface and the tail sticking out of the ground. Another Blanchland witness, Alan Murray – also around 11 or 12 years old – said that the next day the entire aircraft had disappeared into the bog, leaving barely a trace of evidence it had been there at all. A third eyewitness, Harold Forster of Crawleyside, Stanhope had tried to visit the crash site with his young friends, but by that time the RAF guards were on the scene and chased the lads away. Decades later, Harold provided a rough sketch of the crash site which proved to be almost exact.

The RAF was on site for two days recovering P/O Appel’s body for burial at Sutton Bridge, South Lincolnshire. And for two-thirds of a century, until Sunday, 9 March 2008, the Spitfire remained hidden in its peatbog grave on the moor.

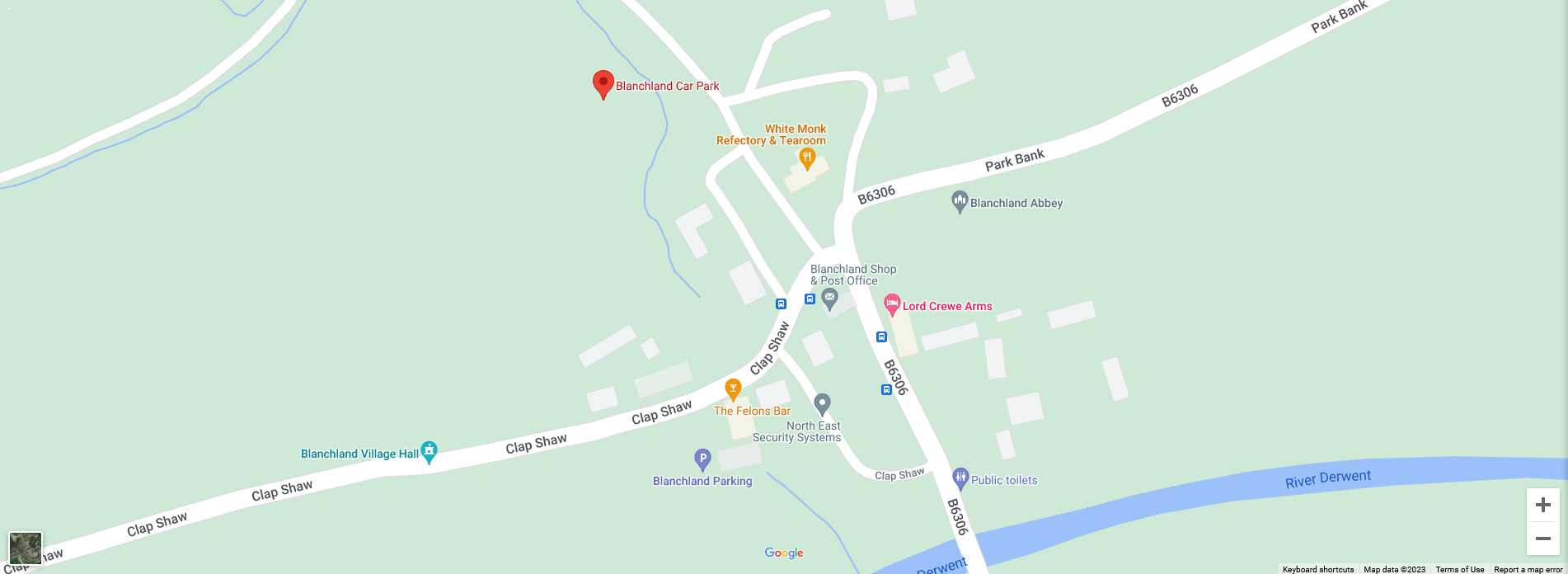

The ACIAs Philip Smith – a postman from Whickham – had spent months trying to locate the exact site the plane went down, finally finding it in January 2007 with the help of witnesses like Tommy, Alan and Harold. After lengthy talks with the MOD, landowners Lord Crewe’s Charity, Natural England and Durham County Council, Philip had permission to carry out an excavation at the site.

Sunday March 9 2008 dawned freezing cold and bright, a brief sunny window in what was a pretty miserable week of weather. The ACIA group picked their way carefully over the tough moorland terrain of heather, peat bogs, pale blond tussocky grass and cushions of bright green sphagnum moss. As the moorland was a Site of Specific Scientific Interest (SSSI) – a rich peatland habitat for all kinds of increasingly rare plants and wildlife – the excavation would have to be hand shovels only – no damaging mechanical diggers.

Durham County archaeologist Deborah Anderson (pictured left) was on hand to ensure the digging kept within the parameters of the area originally damaged by the plane’s impact and that everything was put back as it had been. A scan with a detector confirmed a large body of metal below the boggy surface, and the group began the extremely dirty job of lifting off the mud, clod by sloppy clod.

A slow start at first, just pieces of wood, possibly the shoring from the RAF’s dig to recover P/O Appel’s remains. Then suddenly pieces of the wreckage start coming up thick and fast – a fuel cap, an ammunition box lid, a brass oil filter as pristine as the day it was made, and sections of bent fuselage with the dark green paintwork still clearly visible. Clearly the sodden, airless bog has provided the perfect conditions for preserving the Spitfire; the artefacts would have looked just the same had 6,000 years elapsed, never mind sixty.

Two very poignant finds were the radio controller complete with red push buttons, and the length of hose that leads from the pilot’s air supply to his mask.

All fragments are painstakingly washed, photographed, labelled and logged. Most will go to an aircraft museum, but it would be nice, says Jonathan Shipley of the ACIA, if some could come back to the area to go on display locally at some point.

Philip Smith said: “As time goes on, future generations could forget how the Second World War affected everyday life, even out here far away from the cities. The ACIA carries out these archaeological excavations at crash sites so that the enormous contribution and sacrifice of young pilots like Harold John Appel are never forgotten.”

Philip Smith of the Air Crash Investigation and Archaeology group holds the hose that would have led from the pilot’s air supply to his mask.